Traversées polaires : comment préparer une aventure en Arctique ou en Antarctique

Why polar crossings fascinate me

Polar crossings – whether in the Arctic or in Antarctica – combine everything I love about adventure travel: wild landscapes, demanding logistics, and a genuine sense of exploration. When I talk about a “polar crossing”, I usually mean a long, self-supported journey over ice and snow, often pulling a sled (a pulk) and moving day after day in extreme conditions. These trips can range from guided expeditions to the North Pole to ambitious Antarctic ski traverses.

In this article, I want to walk you through how I prepare for an Arctic or Antarctic adventure: from fitness and gear to logistics, safety, and mental readiness. My goal is to give you a realistic picture of what a polar expedition involves and help you decide if this kind of trip is right for you – and, if it is, how to get ready step by step.

Arctic vs Antarctic expeditions: understanding the differences

Before planning a polar trip, I always start by clarifying the destination. The Arctic and Antarctica are both polar regions, but they are very different environments and require specific approaches.

In the Arctic, I travel on a frozen ocean, surrounded by landmasses like Greenland, Canada, and Russia. Sea ice moves, cracks, and forms pressure ridges. Wildlife is part of the equation: polar bears, seals, whales, arctic foxes. Weather can be highly variable, with storms, drifting ice, and the constant risk of leads (open water between ice floes).

In Antarctica, I am usually on a high, cold, dry continent covered by a massive ice sheet. Distances are huge, the interior is almost entirely ice and snow, and the temperatures can be more extreme than in most Arctic trips. There is no threat from polar bears, but the remoteness is unmatched. Evacuation is complicated, and logistics are heavily regulated by international treaties and specialized operators.

When I plan a polar expedition, these differences shape everything: route planning, avalanche and crevasse awareness, wildlife safety, and the type of guiding or logistics I need to book.

Choosing the right type of polar adventure

Not all polar trips demand the same level of experience. When friends ask me how to “start” in polar travel, I usually suggest thinking in terms of progression.

Some common types of Arctic and Antarctic trips include:

- Introductory Arctic tours: Short snowmobile or dog-sled outings, or a few days of skiing with a guide near towns like Longyearbyen (Svalbard), Tromsø (Norway) or Ilulissat (Greenland).

- Guided polar expeditions: Multi-day or multi-week ski tours pulling sleds, often crossing parts of Svalbard, Greenland ice sheet sections, or routes towards the North Pole or South Pole, supported by a professional guide and logistics team.

- Ski traverses and crossings: More ambitious polar crossings involving hundreds of kilometers, usually self-supported or semi-supported, which demand solid winter camping skills and endurance.

- Fly-in “last degree” expeditions: Flying close to the pole and skiing the last degree of latitude (for example, the “Last Degree to the North Pole” or “South Pole Last Degree”). These offer a taste of polar travel without the months-long approach.

I choose the style of trip according to my experience, the time I have available, and my tolerance for risk and discomfort. If I am new to winter expeditions, I start small and build up to more remote polar crossings.

Physical preparation for Arctic and Antarctic crossings

A serious polar expedition is physically demanding. Day after day, I may ski for 6 to 10 hours, pulling a sled weighing 30 to 60 kg (or more) in cold temperatures and often in soft snow. My training reflects this reality.

I focus on:

- Endurance – I build a strong aerobic base with long hikes, running, cycling, or ski touring. I aim for several hours of moderate effort sessions per week.

- Strength and core stability – I work on legs, back, and core to handle the constant pulling motion. Exercises like deadlifts, squats, lunges, planks, and rowing machines make a big difference.

- Specific sled-pulling training – Whenever possible, I simulate the sled pull by dragging a tire or loaded sled on a harness along a trail or beach. This is one of the best ways I have found to prepare my body for polar travel.

- Flexibility and injury prevention – I add mobility work and stretching to prevent overuse injuries, especially in hips, knees, and lower back.

For a demanding polar crossing, I usually start structured training at least six months before departure, gradually increasing volume and adding more specific sessions as the trip approaches.

Mental preparation and mindset

Physical fitness is critical, but my mindset often matters just as much. Polar travel is repetitive: wake up, melt snow, eat, ski, set up camp, repeat. Conditions can be harsh: whiteouts, strong winds, extreme cold, and frustrating progress when the ice drifts against my direction.

To prepare mentally, I try to:

- Practice discomfort – I spend nights camping in winter, train in bad weather, and get used to being cold and tired while remaining focused.

- Develop routines – On expedition, routines keep me efficient and safe. I rehearse packing, setting up the tent, and managing layers until it becomes automatic.

- Set realistic expectations – I remind myself that not every day will feel like a heroic adventure. Many days will be slow and monotonous, and that is normal.

- Build teamwork skills – If I join a guided group or team expedition, good communication, patience, and conflict management are essential to keep morale high.

Essential gear for a polar expedition

Choosing the right polar expedition gear is one of the most time-consuming aspects of my preparation. In these environments, equipment is not a luxury; it is a safety system. While every packing list varies depending on the route and operator, I always think in categories.

Clothing and layering system

- Base layers in merino wool or technical synthetic fabrics, top and bottom.

- Insulating mid-layers: fleece, light synthetic jackets, or wool sweaters.

- Outer shell layers: windproof and waterproof jackets and trousers with robust zippers and reinforcements.

- Expedition down parka for breaks and camp.

- Multiple gloves and mittens: thin liners, insulated gloves, over-mitts with windproof shells.

- Warm hats, balaclavas, and neck gaiters to protect the face from frostbite.

- Insulated over-boots or gaiters, plus vapor barrier liners or double boots for extreme cold.

Camping and survival equipment

- Four-season tent with strong poles and snow flaps.

- Two sleeping pads (closed-cell foam plus inflatable) for insulation from the ice.

- High-quality sleeping bag rated for temperatures well below expected lows.

- Reliable stove (often liquid fuel like white gas) and multiple fuel bottles, plus repair kit.

- Lightweight but robust cooking set and insulated containers for hot drinks.

Travel and safety gear

- Ski touring or Nordic touring skis with bindings designed for polar travel.

- Skins or traction solutions suitable for long days and mixed snow conditions.

- Pulk (sled) with rigid poles, harness, and secure packing system.

- Navigation tools: GPS, map, compass, and altimeter, plus spare batteries.

- Satellite phone, GPS tracker, or emergency beacon, depending on the operator’s requirements.

- Polar bear deterrents and safety systems in the Arctic (flares, rifle, or other region-appropriate measures, usually managed by the guide).

Because gear requirements change fast, I always double-check the equipment list provided by my expedition company and invest in a few critical items myself, such as base layers, boots that fit perfectly, and gloves that I have tested extensively.

Food, hydration, and energy management in the cold

In polar conditions, I burn a huge number of calories each day, sometimes 5,000 to 6,000 or more. Eating enough becomes a daily challenge. I tend to prioritize foods that are:

- High in calories and fats, such as nuts, cheese, salami, butter, and energy bars.

- Easy to prepare with boiling water, like freeze-dried expedition meals.

- Packaged in cold-resistant wrappers that do not shatter or become impossible to open.

I also pay close attention to hydration. In extremely dry and cold air, I dehydrate quickly without noticing. Melting snow is time-consuming and fuel-intensive, so I try to:

- Drink hot water or tea at every break.

- Use insulated bottles or bottle covers to prevent freezing.

- Monitor urine color to check for dehydration.

On longer expeditions, I work with my guide or logistic provider to plan calorie-dense, varied menus, and I always test some foods at home to make sure I actually like them after many days in the cold.

Logistics, permits, and choosing an operator

One of the most complex parts of Arctic and Antarctic trips is logistics. Access to polar regions is tightly controlled, and conditions can change rapidly. For most people, including me, working with a specialized polar expedition operator is not just convenient – it is essential.

When I evaluate an expedition company, I look at:

- Experience and safety record in the region I want to visit.

- Guide qualifications, including polar travel, first aid, and rescue training.

- Logistical support: resupplies, emergency evacuation plans, contact with air operators or ships.

- Environmental standards and adherence to Arctic and Antarctic regulations.

Depending on my destination, I may need permits, insurance with specific polar evacuation coverage, and medical checks. For Antarctica, most travel is organized through a small number of licensed logistics providers who coordinate flights to ice runways and support on the continent. For the Arctic, regulations vary by country, so I rely on local operators who understand the legal and environmental framework.

Risk management and safety in polar environments

Polar crossings inherently carry risks: extreme cold, frostbite, hypothermia, crevasses, sea ice instability, storms, and wildlife. I never underestimate these dangers, and I build safety into every layer of the trip.

My risk management focus includes:

- Medical preparation – comprehensive first-aid kit, knowledge of cold injuries, personal medications, and a pre-trip medical check.

- Emergency communication – clear evacuation plan, satellite communications, and pre-arranged check-in schedule.

- Route planning – understanding crevasse zones, sea ice charts, weather forecasts, and daily mileage goals that leave margins for bad days.

- Training with my guide – practicing self-rescue techniques, tent anchoring in storms, and what to do if gear fails or someone gets injured.

Going with an experienced polar guide dramatically reduces my personal workload in these areas, but I still take responsibility for understanding the risks and staying proactive about my own safety.

Environmental responsibility and ethics

Every time I travel to the polar regions, I am acutely aware that these are fragile ecosystems already under pressure from climate change. Ice is thinning, wildlife patterns are shifting, and human presence has an impact, even when carefully managed.

To minimize my footprint, I aim to:

- Travel with operators who respect environmental guidelines and international agreements.

- Avoid leaving any waste behind, including micro-trash like torn packaging or broken gear.

- Respect wildlife viewing distances and never feed or approach animals.

- Use high-quality, durable gear that I can repair and reuse instead of replacing frequently.

For me, a successful polar expedition is one where I return with unforgettable memories and photos, but I leave almost no trace behind on the ice.

Getting started with your own polar crossing

If you are thinking about your first Arctic or Antarctic adventure, my advice is to treat it like a multi-year project rather than a last-minute holiday. Start with winter camping trips closer to home, join shorter guided ski tours in cold regions, and slowly build your skills in navigation, cold-weather clothing management, and camp routines.

From there, you can move on to more ambitious guided polar expeditions, such as a Greenland ice cap crossing or a South Pole ski journey. Along the way, invest in key pieces of polar expedition gear, refine your training plan, and learn from experienced guides and teammates.

Preparing properly takes time, but that is part of the reward. When I finally step onto the ice with my sled behind me and a long horizon ahead, I know that every hour of planning, training, and gear testing has brought me to this moment. In an environment as demanding as the polar regions, that preparation is not only the key to enjoying the journey – it is the key to coming home safely to tell the story.

Aventurer en jungle tropicale : guide pratique pour explorer les forêts les plus sauvages du monde

Aventurer en jungle tropicale : guide pratique pour explorer les forêts les plus sauvages du monde  Microaventures près de chez vous : comment vivre l’aventure sans quitter votre région

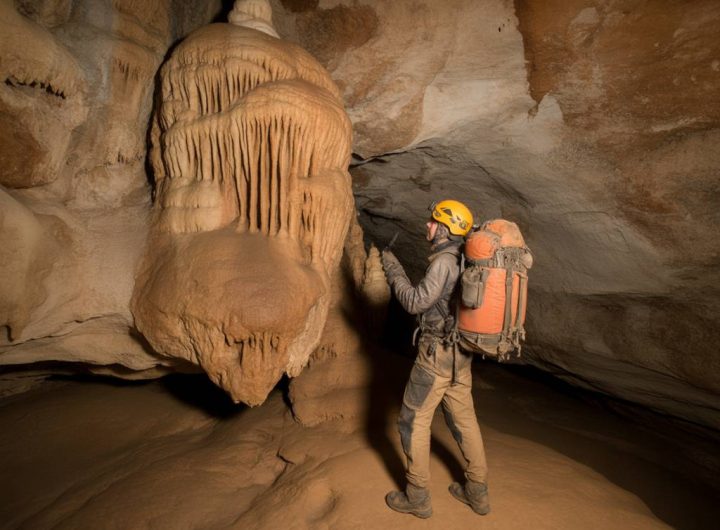

Microaventures près de chez vous : comment vivre l’aventure sans quitter votre région  Caving Adventures: Exploring the World’s Most Fascinating Underground Destinations

Caving Adventures: Exploring the World’s Most Fascinating Underground Destinations  Exploring Volcanic Landscapes: Top Adventure Destinations Around Active Volcanoes

Exploring Volcanic Landscapes: Top Adventure Destinations Around Active Volcanoes  Top 5 adventure watches with gps and survival features

Top 5 adventure watches with gps and survival features  How to choose the right adventure clothing for every climate

How to choose the right adventure clothing for every climate  Traversées polaires : comment préparer une aventure en Arctique ou en Antarctique

Traversées polaires : comment préparer une aventure en Arctique ou en Antarctique